This week’s Perspectives is an interview with Monique, a former elementary school educator living in the Midwest. Monique resigned this year after a 25-year teaching career to do something completely different with her life.

Monique shared her story with me via an interview. I opted to retell her story as a first-person narrative, and the interview was edited for length and clarity. Details have been changed for Monique’s privacy.

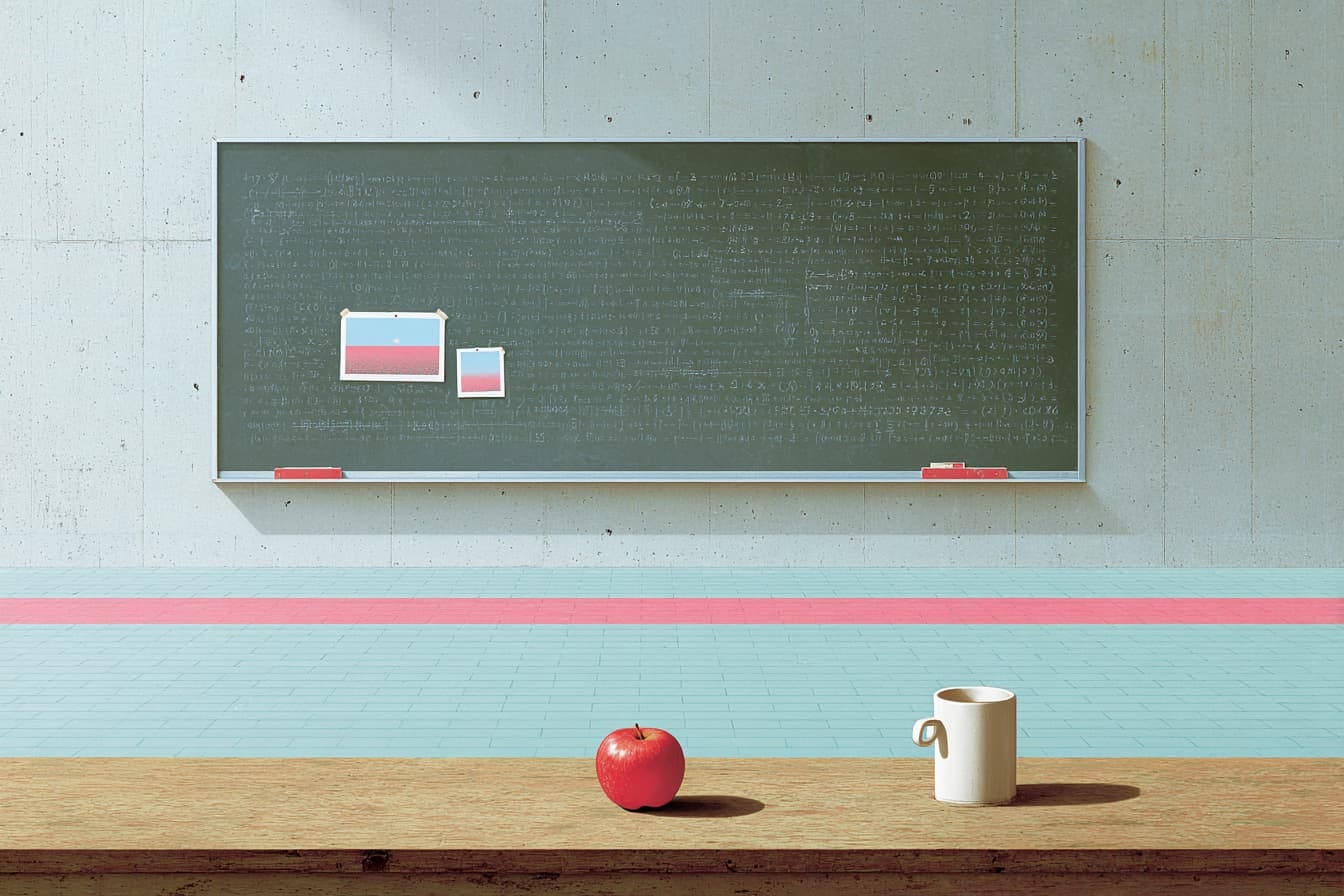

The majority of my life, I wanted to be a teacher. As a kid, I would set up my stuffed animals around a desk and chalkboard in the basement. I didn't have any siblings, but growing up I babysat and had opportunities to work with younger grades in sports groups. People kept telling me how good I was with other people and explaining things. I loved watching people learn and having a hand in that.

I got to the point where I was choosing where to go to college and what to study. I ended up in elementary education. And even when I was given the opportunity to be in another country doing something else, with everything paid for, I told my family that I needed to teach.

I was in education for 25 years. In the beginning, it was exactly what I hoped it would be. There was a lot of freedom to be creative and to meet students where they were at and find their interests. I happened to be at a place with a very involved, supportive parent population. Kids came in and were excited about learning. There was normal "kid stuff" but they treated each other with kindness. Not everything was prescribed for me, nor did the kids have as many assessments or use as much technology as they do now.

Over the past 25 years, best practices and instruction have changed a lot — like what we know about the brain and how people learn. One thing that's different now is that we know kids' brains are wired differently than they were at the time due to the way we live our lives now. Whether that's due to trauma, or the COVID experience, or because of technology, we know that kids are learning differently. And I feel like we, in the education profession, have not changed.

I read somewhere that we are preparing kids for a workforce that existed decades ago instead of the one that's going to exist when they enter the workforce. I think that's exactly right. Obviously, we'll have to wait and see. But school is definitely not set up in a way that's promoting the things I think we need to promote for kids.

One of the things that was a big push at the beginning of my career was that you could use any instructional strategy. Your depth of content knowledge wasn't as significantly important to your instruction as your pedagogical knowledge. "If you know how to teach, you can teach anything" was kind of the way we looked at it. Elementary teachers didn't master any specific content in our undergrad work, because we didn't have to.

But content knowledge matters when you're teaching a six-year-old. Because if you start to say things to kids that don't make sense, kids have to unlearn what they were previously taught. So content knowledge became far more important.

We also understand that kids learn in different ways. Teaching a person to swim is probably the best analogy. Let's say you have 25 kids in front of you in a pool. Some of them have never been in the water, and some of them have been swimming their entire lives. As a teacher, you're expected to know which kids need your hand under their bellies to keep them above water and which should be doing laps and flips turns.

If you're able to differentiate by content, by interest, by readiness level — and, in some subjects, it's easier than others — amazing. You provide the kids with what they need when they need it. The thought that you could do that in every content area, every single day, for every single student, is virtually impossible. There's support staff, interventionists, and special ed teachers, but the struggle is to make sure everyone's on the same page. Assuming I even have enough people, which is usually not true, how do I make sure all of us are expecting the same things in the way a child needs it?

Every year, I would say, "I don't know what I want to be when I grow up." That thought got really serious within the last five years. COVID happened, and the timing was a coincidence, except that I think COVID caused a lot of people to reprioritize their lives. I am probably different as a result of that.

When other job opportunities would open up within the school district, I was always willing to throw my name into the hat. I was at six or seven schools throughout my career, at every grade level. I did two out-of-classroom positions. I would consider leadership positions. With each of these moves, I was trying to figure out where I was supposed to "fit."

I think the way I was treated by children was a significant breaking point. It's going to sound really selfish — and I don't mean it to — but in the beginning, kids were excited to come to school. Even if they didn't like school, they were connected to each other and the staff. They knew they were there because they were going to learn something, and it was going to help them enjoy their lives. Even if all they looked forward to was recess and lunch.

I feel like what's happened over the course of recent history is the amount of trauma that kids have experienced. The way the world works right now is causing them to have a very different outlook on how you treat other people, how you demonstrate an interest in things, and what you do when those things are not true. So, for example, if I'm not connected to someone, what's the base level for how I treat them? If I'm not interested in a subject, what's the appropriate way to demonstrate that?

When I started thinking about equivalents, initially, I wanted a financially equivalent job. I thought I could work with a park district, a day care, a YMCA, or a library. Then I started to think about the skills I have that are not specific to education, like organizing data, organizing events, and getting people connected to each other. I looked at roles that had an organizational management type of label. But none of those doors ever seemed to open.

At this point, I'm more open to more things than I was before because, clearly, the thing I thought I was supposed to do did not work. Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. You have to do something different. I'm a little more open to what's coming to me versus going out and seeking what I think I'm supposed to have.

I'm working at a couple of gyms. Trying to do something with music. And I have a job working outdoors — a job that I had no idea would be fun. My work days are broken up a lot more. There's a lot more physical labor. There's a lot less money. But I'm far more satisfied with the work. And feel more valued, which seems bizarre.

When the school year starts in the fall, I think I'll miss the friendships. It's not going to be setting up my classroom. It's not going to be pulling all the data and making sure I know who needs what before they even walk in the door. It's not sitting in meetings. But I've lost touch with people who are my best friends in the world for the past two and a half decades. And it's not because I don't want to see them. When you're a teacher, you're going to see everyone again in three months when the summer is over. I think that will be hard. But the "Sunday Scaries"? They don't exist anymore.

I think teachers work really hard. I know everybody's job is hard, and hard looks different in a lot of ways. But if you haven't been a teacher or lived with a teacher, you don't understand the incredibly invasive permeation into your entire life. You don't even realize it yourself until you walk away. It's constantly on your mind because you care. You wouldn't have gotten into this profession if you didn't.

Teachers are told that teaching is a work of the heart. A calling. Which is a very sweet way to say, "You're not going to get compensated" or "You're not going to be appreciated." We're told to think that's ok because you're doing it out of the goodness of your heart. And everyone has a breaking point if you're doing something on that basis.

Most issues of this publication are free because I love sharing ideas and connecting with others about the future of work. If you want to support me as a writer, you can buy me a coffee.

If you love this newsletter and look forward to reading it every week, please consider forwarding it to a friend or becoming a subscriber.

Have a work story you’d like to share? Please reach out using this form. I can retell your story while protecting your identity, share a guest post, or conduct an interview.